By Boo Kok Chuon The National Gallery Singapore currently hosts an exhibition entitled “Laws of Our Land: Foundations of a New Nation” (“Exhibition”), showcasing three key laws that shaped modern Singapore. One of these laws is the Women’s Charter. The foundation of Singapore’s family law can be traced back to the inception of English law

By Boo Kok Chuon

The National Gallery Singapore currently hosts an exhibition entitled “Laws of Our Land: Foundations of a New Nation” (“Exhibition”), showcasing three key laws that shaped modern Singapore. One of these laws is the Women’s Charter. The foundation of Singapore’s family law can be traced back to the inception of English law through the extension of the First Charter of Justice, initially introduced in Penang, and later extended to Singapore and Malacca through the Second Charter of Justice 200 years ago in 1826. This set the baseline of our legal system, making English common law the foundational basis for governing marriages.

As a multicultural South East Asian society, the diverse customary and religious practices governing marriages in Singapore meant that the introduction of English law, which was historically shaped by Christian values and assumptions, was not directly applicable.

This difficulty is recognised in Regina v Willans (1858), where the court affirmed that English law formed the general foundation of the legal system in the Straits Settlements, but that its application was not absolute. Rather, English law would apply only to the extent that it was suitable to local circumstances, particularly in areas such as marriage and family relations, which were deeply influenced by local customs and culture.

The approach was further reinforced in Chong Cheow Neoh v Spottiswoode (1869), where Maxwell CJ acknowledged that while English law formed the basis of the legal system, it could not be applied indiscriminately to local communities, particularly in relation to matters of marriage and divorce, which were deeply shaped by religion and custom. This resulted in a fragmented system, with a patchwork of local legislation comprising different ordinances and rules that sought to accommodate the needs of different cultures.

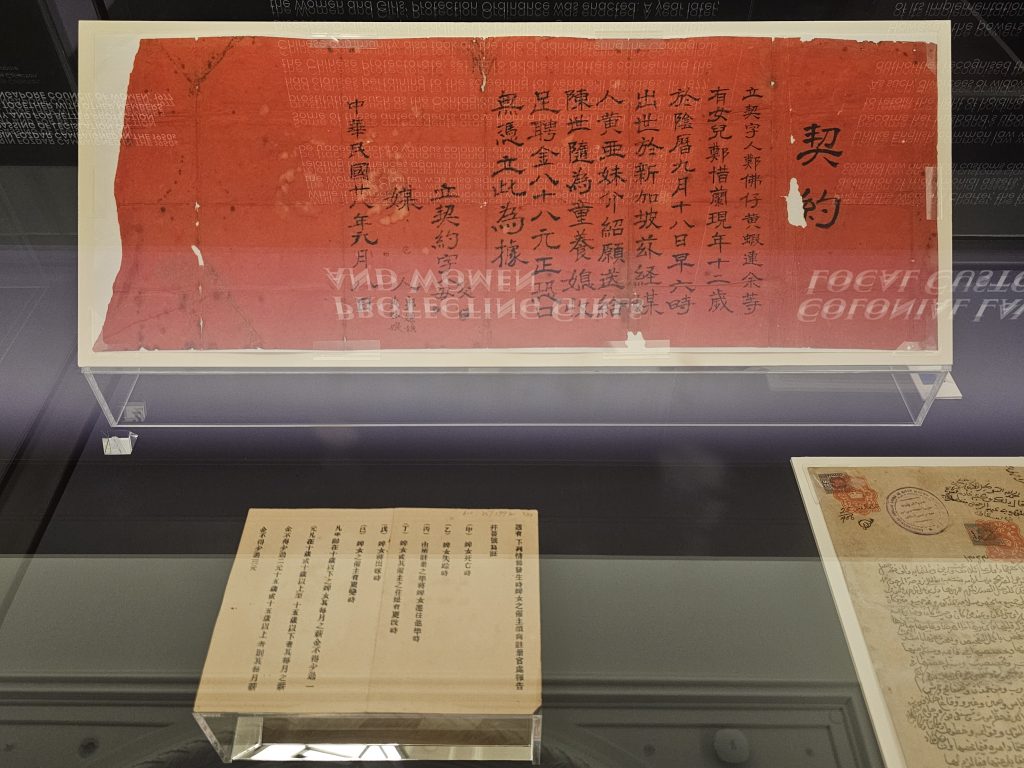

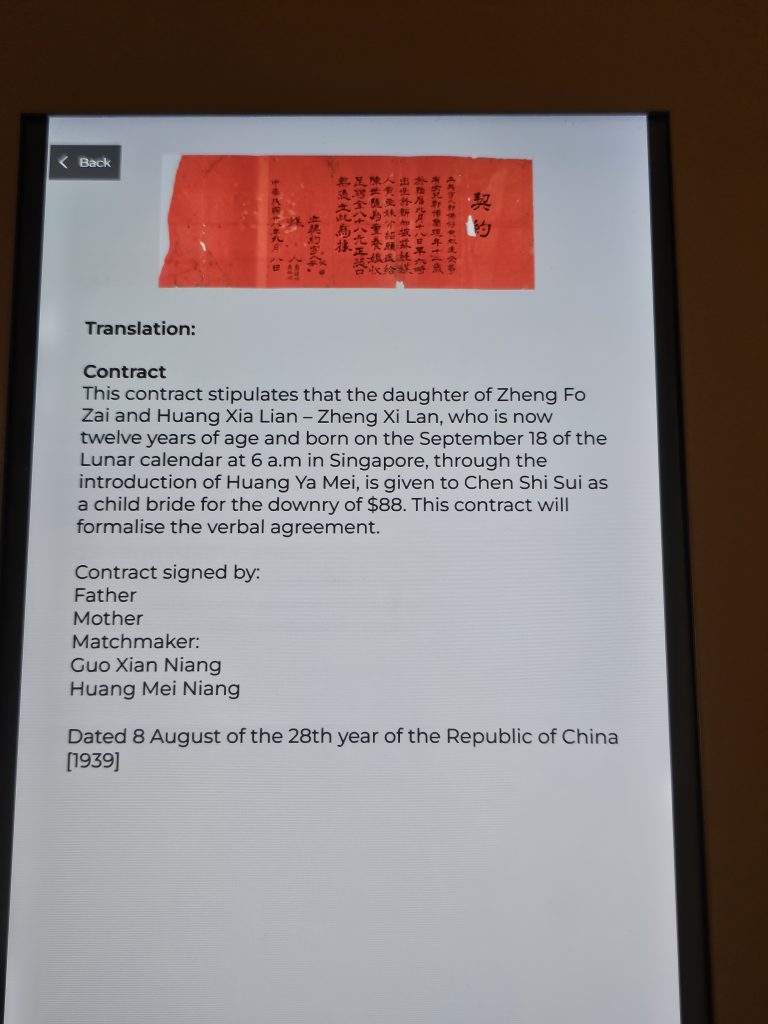

Women’s status during the late 19th century Singapore was unequal in practice, with women and girls often facing structural vulnerability in family arrangements and limited access to effective legal protection, which later reforms sought to remedy. One of the artefacts on display at the Exhibition shows a Chinese marriage contract dated 1939, which formalised the endowment of a 12-year-old girl as a child bride, facilitated by matchmakers and a specified dowry as “considerations”.

Figure 1 Artefact of a Marriage Contract in 1939. Photo taken by author on 24 January 2026 ©

This artefact illustrates that women and girls could be structurally vulnerable, as marriage arrangements were negotiated by adults rather than entered into voluntarily. It shows how women and girls could be treated as subjects of familial arrangement and exchange.

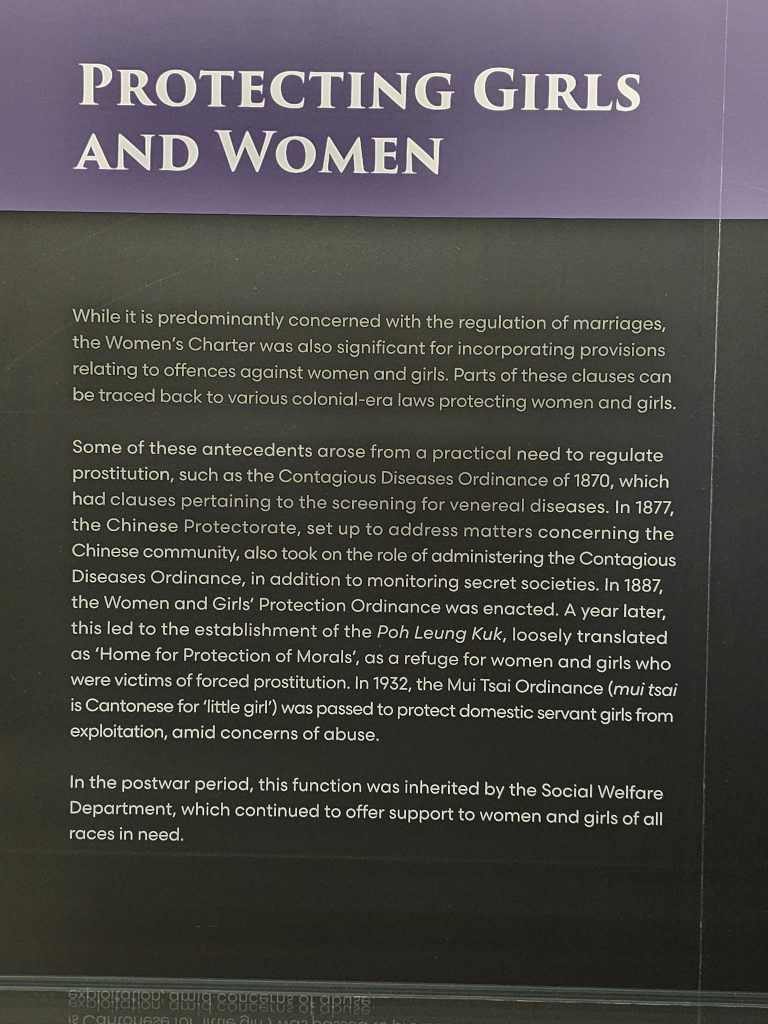

The Exhibition also traces the development of legal protection for women and girls through earlier legislations such as the Women and Girls’ Protection Ordinance 1887 and the Mui Tsai Ordinance 1932, which were enacted to address forced prostitution and exploitation of domestic servant girls. These historical realities provide important context for understanding the Women’s Charter 1961 as a remedial and protective statute aimed at strengthening equity and safeguarding vulnerable persons.

The enactment of the Women’s Charter 1961 marked the third stage of Singapore’s family law development, representing a decisive shift from a fragmented patchwork of ordinances towards a unified and modern framework governing non-Muslim marriages.

The Women’s Charter 1961 marked a decisive shift towards a unified framework governing non-Muslim marriages. When the PAP government came into power, one of its key reform agendas was to modernise family law and raise the status of women within society. This objective was ultimately enshrined in section 46 of the Women’s Charter 1961, which imposes a reciprocal duty of maintenance between husbands and wives. This shifted away from traditional assumptions of women as merely dependent spouses, and towards a framework that recognises women as equal partners within the family unit, entitled to legal protection and enforceable support where necessary.

Section 49 of the Women’s Charter 1961 further operationalises this framework by empowering the court to order a man to maintain his wife or former wife where it is just to do so, thereby strengthening the enforceability of spousal support obligations in circumstances where women were historically vulnerable to abandonment and financial deprivation. Read together, these provisions demonstrate that the Women’s Charter was enacted to elevate women’s protection and standing towards equality and equity, rather than to place women on a higher legal status than men.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *